Aparna

Published on

12 - 10 - 2019

Aparna

Published on

12 - 10 - 2019

As the year draws to a close and my family enters cookie baking mode, I’m thinking about a harder nut to crack than chestnuts on an open fire: white-led conservation and outdoor nonprofit boards.

We’ve noticed that in their urgency to diversify, many conservation and outdoor nonprofit boards have been clamoring to recruit more people of color. More and more, we’re interacting with boards that have successfully identified and enlisted board members of color.

But we’re also noticing that despite the best of intentions, board diversification isn’t the solution to addressing structural equity, inclusion and justice issues.

Here are some of the problems with a myopic focus on diversifying your board.

1. It’s incredibly tokenizing

To know that you were recruited specifically based on your perceived racial or ethnic identity—even if you’re also a whiz with numbers, a legal genius, a talented fundraiser, or a network builder—can feel tokenizing.

To know that you were recruited specifically based on your perceived racial or ethnic identity—even if you’re also a whiz with numbers, a legal genius, a talented fundraiser, or a network builder—can feel tokenizing.

To address this, be clear and authentic on the “why” for recruiting a black, indigenous, or person of color (BIPOC). Otherwise they can feel like they’re window dressing.

2. It’s isolating to be the only one

A colleague talked to me once about how hard it is to be “the only chocolate chip in the cookie.” It can be incredibly isolating to be the one BIPOC in white board, especially if you have starkly different experiences or connections to conservation and the outdoors than your peers.

A colleague talked to me once about how hard it is to be “the only chocolate chip in the cookie.” It can be incredibly isolating to be the one BIPOC in white board, especially if you have starkly different experiences or connections to conservation and the outdoors than your peers.

To address this, make sure you recruit multiple BIPOC (sometimes called “cluster hiring” in the non-board world) so there isn’t just one BIPOC on the board.

3. One person can’t speak for an entire people

Just because I am a brown person does not mean I can speak to all experiences of brown people. BIPOC are not a monolith, and there is incredible diversity even within my own South Asian Indian immigrant community. Asking one person to tell the story of an entire community only reinforces that there is a single story describing our community, fueling stereotypes that continue to plague our sector. It also fuels solutions privilege: the expectations that BIPOC board members will provide solutions to white-led nonprofits’ struggles with justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI).

Just because I am a brown person does not mean I can speak to all experiences of brown people. BIPOC are not a monolith, and there is incredible diversity even within my own South Asian Indian immigrant community. Asking one person to tell the story of an entire community only reinforces that there is a single story describing our community, fueling stereotypes that continue to plague our sector. It also fuels solutions privilege: the expectations that BIPOC board members will provide solutions to white-led nonprofits’ struggles with justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI).

To address this, ask all board members to speak from their own experiences and not represent any one group or communty, and make sure all board members (regardless of identity) have a role in JEDI work.

4. Just because they’re a person of color doesn’t mean they can do JEDI work, or are even bought into JEDI

White-led nonprofits often assume that as BIPOC, our lived experiences qualify us to engage in the complex and nuanced work of JEDI. It has taken time, effort, a lot of learning, humility, and self awareness in spades for me—someone who does this work for a living—to even feel comfortable touting myself as an expert. Being brown didn’t automatically confer a “degree in JEDI” upon me, and it doesn’t for anybody else.

White-led nonprofits often assume that as BIPOC, our lived experiences qualify us to engage in the complex and nuanced work of JEDI. It has taken time, effort, a lot of learning, humility, and self awareness in spades for me—someone who does this work for a living—to even feel comfortable touting myself as an expert. Being brown didn’t automatically confer a “degree in JEDI” upon me, and it doesn’t for anybody else.

Folks also assume all BIPOC are bought into JEDI. Unfortunately, there are ways that we as BIPOC can be complicit in racism and oppression. Just because we are not white doesn’t mean we don’t have biases and privilege as it relates to so many other identities. And even BIPOC have internalized racial oppression which causes some of us to behave in ways that hurt other BIPOC (e.g., purporting to not see color; not recognizing the need for affinity spaces; engaging in tone policing and respectability politics of our fellow BIPOC).

The bigger issue is that white folks have a great degree of trust in what BIPOC have to say about JEDI work. What we say is gold. And this can be insidious and harmful. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve heard something along the lines of: “even board member Joe thinks we shouldn’t create an internship program for people of color; he’s a person of color who made his way into leadership without a special program and doesn’t think they’re needed!” Unfortunately, board member Joe probably hasn’t done his work to understand why programs like this are necessary, or why his bootstrap mentality is problematic. So it actually does an organization a disservice when they enlist a BIPOC who is not bought into the work.

To address this, when onboarding any new board member, ask them about their commitment to JEDI work to ensure they are bought in, and ask them about their experiences engaging in JEDI work to ensure they are competent.

5. Representation is not the same as culture change

Representation is only one small dimension of a holistic JEDI effort. No amount of adding BIPOC to boards (or staff, for that matter) will make organizations or the outdoor/conservation movement more inclusive or equitable or just.

Representation is only one small dimension of a holistic JEDI effort. No amount of adding BIPOC to boards (or staff, for that matter) will make organizations or the outdoor/conservation movement more inclusive or equitable or just.

You can invite people to a seat at your table, but as my colleague CJ Goulding says, unless you fundamentally change the shape of that table, that invitation is just paying lip service.

To address this, organizations need to shift culture in order for the BIPOC they recruit to stay. This entails (among many things) reflecting on the whole and untold history of conservation and outdoor recreation, understanding the myriads of ways we connect to and care for more-than-human nature based on our culture and history, not lionizing founders or revering origin stories that are replete with oppression, understanding issues surrounding power and control, and shifting dominant culture to make sure everyone feels a sense of belonging in the workplace.

If you take one piece of advice from this post, let it be this: representation is an important, but small slice of the work. So make sure that your board diversity efforts are part of a larger, more holistic strategy that focuses on culture shift.

By: Aparna Rajagopal, cofounder of The Avarna Group

By: Aparna Rajagopal, cofounder of The Avarna Group

Dear Avarna community, We’re only four months into four years of this presidential administration, and the attacks on everything our…

Read full post about Staying the Course: On EOs, Education, ERGs, and SailingAvarna Community, It is with nearly all the emotions you might find in an emotions wheel that I am announcing…

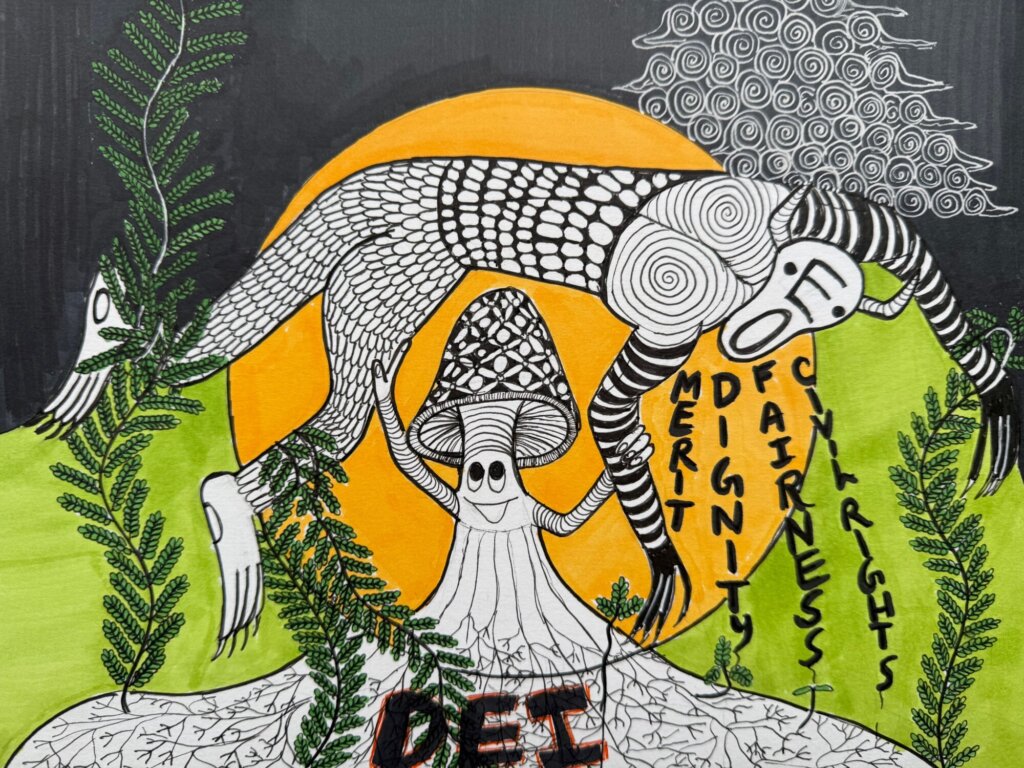

Read full post about Farewell, AvarnaThe current administration’s anti-DEI Executive Orders have sparked varied responses in the nonprofit and private sectors—some organizations are defending DEI…

Read full post about DEI Jujitsu: Flipping the Backlash to Reframe Our Work