Ava

Published on

08 - 21 - 2017

Ava

Published on

08 - 21 - 2017

In the wake of Charlottesville this past weekend, I have been thinking quite a bit about how these events connect to the work our partners and clients do. So, in this third installment of our “connecting the dots,” series, we’d like to talk about monuments and memorials.

Last week the Unite the Right movement rallied against the dismantling of a confederate monument that Charlottesville, Virginia’s residents had voted to take down. The argument for dismantling a Confederate monument seems to be an easy one that is long overdue– the Confederate party fought in service of slavery and supported the institutionalization of anti-Blackness in this country.

But we should also interrogate other ways that we memorialize and erase our U.S. history, especially in our public lands. Last Thursday, indigenous activist Dallas Goldtooth (Dine and Mdewakanton Dakota) encouraged us to not only think about white supremacy as a driver of anti-Blackness, but also as a tool for anti-indigeneity and settler colonialism. In a series of tweets, he notes, that “W[hite] Supremacy in the U.S. is a complex intersection of Anti-Blackness and Settler Colonialism and Imperialism over the ‘Other’….”

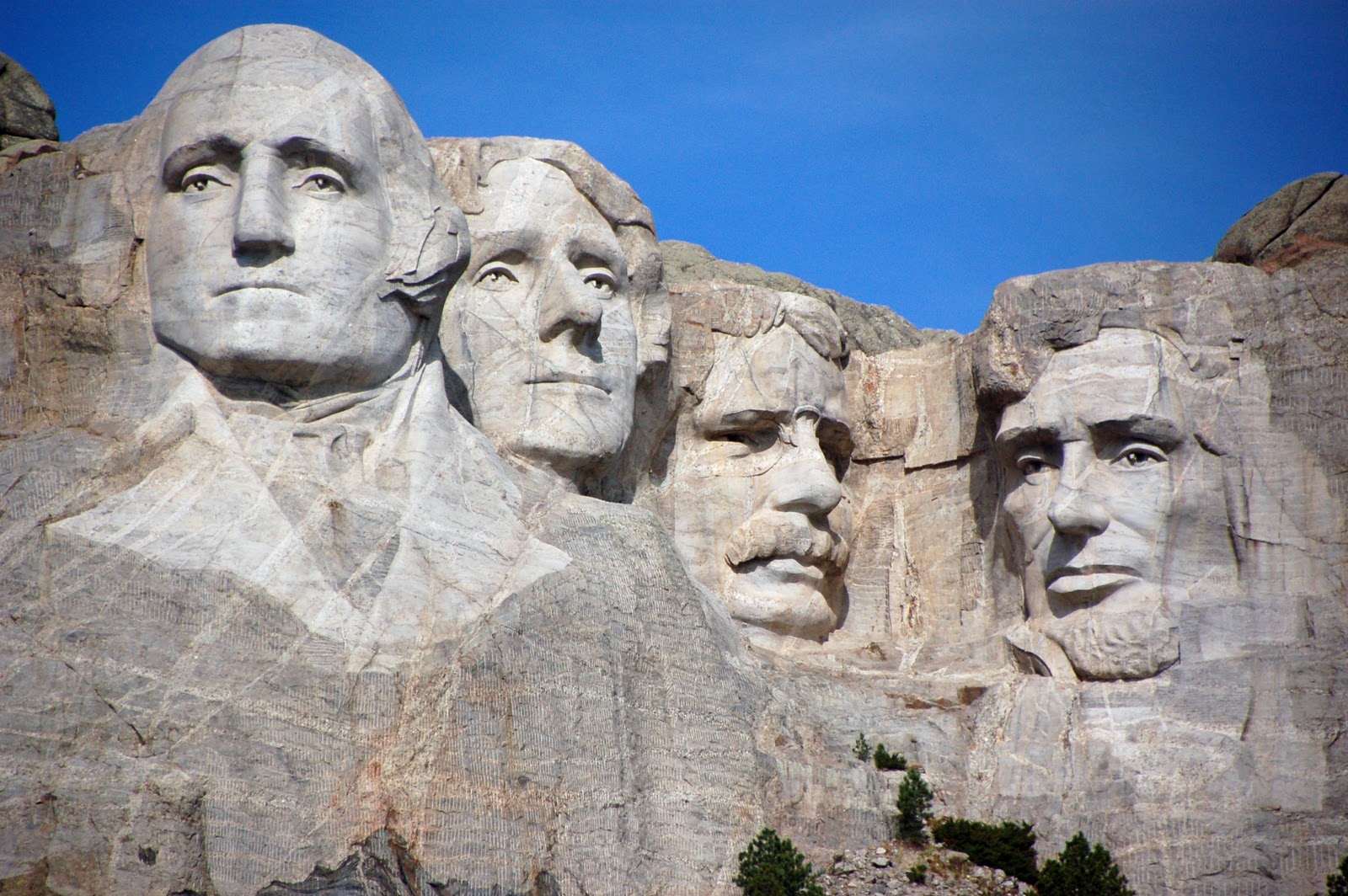

Mount Rushmore is an example of the complex intersection that Goldtooth implores us to recognize. Mount Rushmore was carved into land that was dispossessed from indigenous people in the Black Hills of South Dakota. After the Great Sioux War, the U.S. and several tribes signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which granted land rights to the Great Sioux nation. But when General Custer discovered gold in the area in 1874, the Fort Laramie Treaty was broken and the U.S. took ownership of the land.

In the 1920s, South Dakotan historian Doane Robinson rallied to create a monument to generate more tourism in the state. Ultimately, Gutzon Borglum, a KKK member and the same person commissioned Confederate monument Stone Mountain in Atlanta, Georgia, was commissioned to create the South Dakota monument. It was Borglum who selected the presidents to represent this “Shrine of Democracy:” George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt.

Each of these men who were selected to be memorialized on Mount Rushmore had a hand in perpetuating racism and settler colonialism. Washington and Jefferson owned slaves. Lincoln signed off on legislation that supported the dispossession of indigenous lands. Roosevelt, perhaps the most recognizable to the conservation world, is lauded for conservation efforts that in fact had a negative and rippling impact on African American and indigenous people’s land, water, and hunting rights. All expressly communicated racist ideologies at various times during their presidencies.

Though I could go on for days (and in fact, historians have) about the lesser known history of Mount Rushmore, the point I want to draw out is Confederate monuments are not the only monuments that need to be called into question. Our monuments and memorials are not only reflective of our nation’s history, but also our values. The choice to memorialize four presidents who upheld racism and settler colonialism on stolen land is a part of Mount Rushmore that should be discussed. And as we look forward to creating new monuments, we need to ensure that the way in which we memorialize people, lands, and waters is in service of equity and justice.

Of course, some of this great work is already happening. 2016 was in fact a banner year for creating national monuments through an equity lens; at Stonewall, in Bears Ears, as well as to remember Reconstruction, Birmingham Civil Rights, and the Freedom Riders. But we still have so much work to do… so what does that look like?

If you’re a land management agency, ensure that your interpretation materials reflect the full history of the place you manage, and as proposals for new monuments and memorials come across your desk, ask yourself if and how their construction or protection is in service of equity and justice.

If you’re a land trust or conservation organization, make sure you understand how your land and water conservation or protection efforts are in service of equity and justice. Specifically, ask yourself who historically owned and/or occupied the land, in service of whom you are protecting or conserving the land, and for what activities you are protecting or conserving the land. Additionally, seek out conservation projects that specifically support marginalized communities.

If you’re an outdoor or environmental education organization, ensure that your curriculum includes information about the complex history of the land in which you run your program, as well as time to discuss this history.

And finally, regardless of who you are and the organization you work for, do your homework to better understand these monuments and take an informed stance through the lens of equity when advocating for either their construction or dismantling of national monuments.

Post script:

We pretty much got scooped on this article and idea, which contrary to my academic background, I love. We get to hear similar ideas discussed, layered on top of one another and deepening our understanding. Some other folks who wrote about Mount Rushmore this weekend include:

Wilbert Cooper at Vice: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/9kkkby/lets-get-rid-of-mount-rushmore

Gyasi Ross responds to Cooper: https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/culture/thing-about-skins/native-people-discuss-mt-rushmore-no-dont-blow-stupid-ass-vice-com/

Bethy Squires: https://broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/j55557/mount-rushmores-extremely-racist-history

Dear Avarna community, We’re only four months into four years of this presidential administration, and the attacks on everything our…

Read full post about Staying the Course: On EOs, Education, ERGs, and SailingAvarna Community, It is with nearly all the emotions you might find in an emotions wheel that I am announcing…

Read full post about Farewell, AvarnaThe current administration’s anti-DEI Executive Orders have sparked varied responses in the nonprofit and private sectors—some organizations are defending DEI…

Read full post about DEI Jujitsu: Flipping the Backlash to Reframe Our Work