Ava

Published on

02 - 08 - 2017

Ava

Published on

02 - 08 - 2017

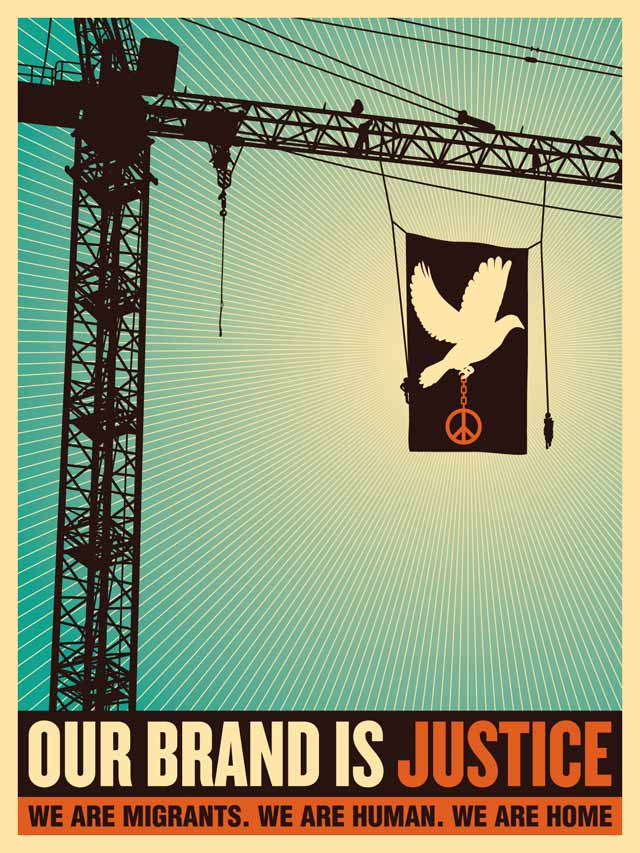

Art featured above by Ernesto Yerena Montejano

Grab some snacks. This is a longer than a usual blog post, but we think all of it matters.

Last July, we wrote a blog post connecting Black Lives Matter to the environmental movement. In our second installment of the Connecting the Dots series, we are connecting issues of immigration and refugees to the environmental movement. In case you haven’t been keeping up with the news, President Trump has issued a flurry of troubling executive orders, including three that relate to immigration and refugees. If you need to catch up, the executive order summaries are here:

In the wake of these orders we have noticed an outcry from many environmental, conservation, and outdoor organizations. Though this has been heartening, we’ve also noticed that few have acknowledged how environmentalism and conservation can actually be complicit in the anti-immigration narrative.

If you don’t think immigration rights are related to your work in conservation, outdoor and environmental education, or environmental advocacy, read on for some ways to connect the dots:

PART 1: History

Anti-immigration sentiments show up early in the history of environmentalism. One of catalysts for America’s love of natural spaces was the See America First campaign, which urged Americans to travel West by the new railroad lines to partake in the natural beauty of the West. What is not talked about in this history is that the railroads were built on the backs of Chinese immigrant laborers, who were paid only two thirds what their White counterparts were paid, and who soon thereafter were banned by executive order from staying in the United States or entering in to the United States. (Interestingly it was this executive order and ensuing litigation that established the President’s plenary power to enforce immigration bans like the bans issued last week).

As modern American environmental movement gained steam in the 1960s, its narrative was partially fueled by the fear of increasing populations and finite resources. The publishing of Elrich’s Population Bomb and Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons popularized the notions that our nation was in dire straits due to an increasing population and our inability to sustainably share natural resources, respectively. Elrich and Hardin’s ideas firmly planted anti-immigration views in the environmental narrative with the theory that more immigrants meant more people in our beautiful, yet finite and delicate natural spaces. This fear, coupled with racist attitudes (particularly toward Latin Americans), made immigrants of color a perceived enemy to environmental causes. In his 1988 essay “Immigration and Liberal Taboos,” environmental icon Edward Abbey galvanizes this theory by arguing that immigration (specifically from the south) will result in a takeover of the U.S. by “millions of hungry, ignorant, unskilled, and culturally-morally-genetically impoverished people” who have an “alien mode of life” that will undermine American culture and values.

The logic that more people (and specifically people of color) equals more environmental degradation is also deeply flawed in that it fails to consider the complexity of human relationships to land and water. We need to remember that lack of environmental protection policy, consumerism, and the commodification of natural resources are at the root of environmental degradation. Indeed, the hyper-focus on immigration as an environmental issue says more about our racial politics than our concern for the environment.

Moreover, we’d be remiss if we didn’t remind our readers that in the wake of several environmental crises, we are in desperate need for innovation and creativity. Abundant research indicates that a diversity of perspectives, backgrounds, and experiences can actually result in increased innovation and more creative problem solving with respect to our environmental crises. So, more people doesn’t equal worse environment. Rather, it equals more solutions to environmental problems.

PART 2: Current Sentiments

For those of you who think we’ve left this history behind us, think again. Troubling views about immigration remain in the environmental movement. For example, it was not until 2004 when the Sierra Club began to deeply examine and debate their long-standing stance connecting immigration to unsustainable population growth that would purportedly cause environmental degradation. And it was only 2013 when they finally explicitly disavowed its anti-immigration stance. Though we are impressed and grateful for the Sierra Club’s transparency around their immigration stance today, as well as their focus on equity and justice, anti-immigrant attitudes and actions persist in our sector. These sentiments manifest in many ways, such as:

PART 3: Impact

Of course these anti-immigration attitudes, actions, and policies continue to impact immigrants and refugees in the environmental world. We’ve listed just a few impacts here:

Now what?

Colleagues and partners, we urge you to own the unsavory history of our movement and resolve not to repeat it. Support your immigrant staff and constituents. Publicly speak out on the executive orders. Make the connection for yourself as to how your organization specifically can leverage your power to support for rights surrounding immigrants and refugees. And finally, identify ways you mission and environmental ethic supports, not disparages, immigrant rights.

Dear Avarna community, We’re only four months into four years of this presidential administration, and the attacks on everything our…

Read full post about Staying the Course: On EOs, Education, ERGs, and SailingAvarna Community, It is with nearly all the emotions you might find in an emotions wheel that I am announcing…

Read full post about Farewell, AvarnaThe current administration’s anti-DEI Executive Orders have sparked varied responses in the nonprofit and private sectors—some organizations are defending DEI…

Read full post about DEI Jujitsu: Flipping the Backlash to Reframe Our Work