Aparna

Published on

04 - 24 - 2019

Aparna

Published on

04 - 24 - 2019

Similar to when Camber Outdoors unveiled its 2019 Pledge, we (Ava and Aparna) have had a lot of thoughts and ideas swirling around in our heads as the #WontTakeSHIFTAnymore campaign has rolled out. We have brains that tend to go into a mode that we lovingly call, “entropic processing overdrive,” in which we have a million constellations of thoughts on several planes, without much of a logical pathway.

But in all of that chaotic processing, we both keep coming back to two things: one related to the substance of campaign, and the other related to the process. First, in these moments when people are sharing impacts of oppression, it is crucial that we bear witness to these narratives of pain and allow them to shape our actions and worldview. Second, movements are built with many approaches, and in this moment it does us more harm than good to question tactics.

To our first point, in our work at the Avarna Group, we often talk a lot about strategies, plans, workshops, and timelines. It can feel very transactional and somewhat devoid of emotion. And it is at times. But perhaps what you don’t know about our work is it is also deeply informed by and rooted in stories, including stories about pain. Because without understanding the real pain that systems of oppression cause, we can lose sight of the work.

Last week, we witnessed many ELPers speaking up and speaking out about the pain caused by their experiences at SHIFT. First and foremost, we should remember that they have not shared their stories because it is easy; they’ve shared their stories because, even with the knowledge of the trolling, gaslighting, and abuse that would ensue, they felt compelled to share them. They needed to share them. It takes courage, resolve, bravery to speak your truth, and speaking your truth in the face of backlash is simply a reflection of the profound heartbreak that the truth teller feels.

So, for those of us who are witnesses to the ELPers’ pain, what is our responsibility?

When someone decides to publicly share their story, it’s incumbent upon all of us to bear witness to it. Bearing witness means sitting with discomfort, affirming peoples’ experiences, and allowing these stories, including the pain expressed within them, to shape us, to be imprinted on our worldview, and to inform our actions. The ways in which these stories shape and shift our worldview will be different for all of us based on who we are. However, we cannot deny each other’s experiences of pain, question these experiences, or otherwise trivialize them, because if we do, we are cutting our movement short.

To our second point, we’ll admit that it’s tempting to react to someone’s social media post with internal questions like “should they have put this out on social media?” “is this the best message?” “why did they use that word?” “are they being inflammatory or hyperbolic?” “will people listen?” Here’s the thing. Movements take on many forms. It does not behoove us, as witnesses, to question tactics used by others. Nor does it help to apply our lens of perfection on someone else’s messaging. Expecting perfection in each other; or expecting others to use the same avenues as you would, can undermine a movement. History teaches us that there are many stories, journeys, and approaches to social justice activism. Movements aren’t borne from one experience or successful because of a single approach.

Aparna sometimes thinks of India’s liberation from British colonialism here. As Gandhi turned a cheek, others were engaging in violent revolution against the British government. And though his act of pacifism is celebrated, the holistic history tells us that India didn’t achieve liberation because of Gandhi. India was liberated through a movement of angry, sad, frustrated, and hurt people who engaged in a variety of tactics: violent, nonviolent, marching, writing letters, one-on-one diplomacy, and more.

So, the bottom line is that there are many ways in which we can engage in JEDI work – how we engage in that work can vary and is riddled with messiness. However, what is clear is that we will get nowhere in movement building if we tear each other down based on process or semantics.

With all of that said, we hope someday to live in a world where people do not have to express their pain to be fully seen; a world where the display and consumption of pain and anger is not the primary way we build movements; rather, our visions and imaginations for liberation are what bind us.

Dear Avarna community, We’re only four months into four years of this presidential administration, and the attacks on everything our…

Read full post about Staying the Course: On EOs, Education, ERGs, and SailingAvarna Community, It is with nearly all the emotions you might find in an emotions wheel that I am announcing…

Read full post about Farewell, AvarnaThe current administration’s anti-DEI Executive Orders have sparked varied responses in the nonprofit and private sectors—some organizations are defending DEI…

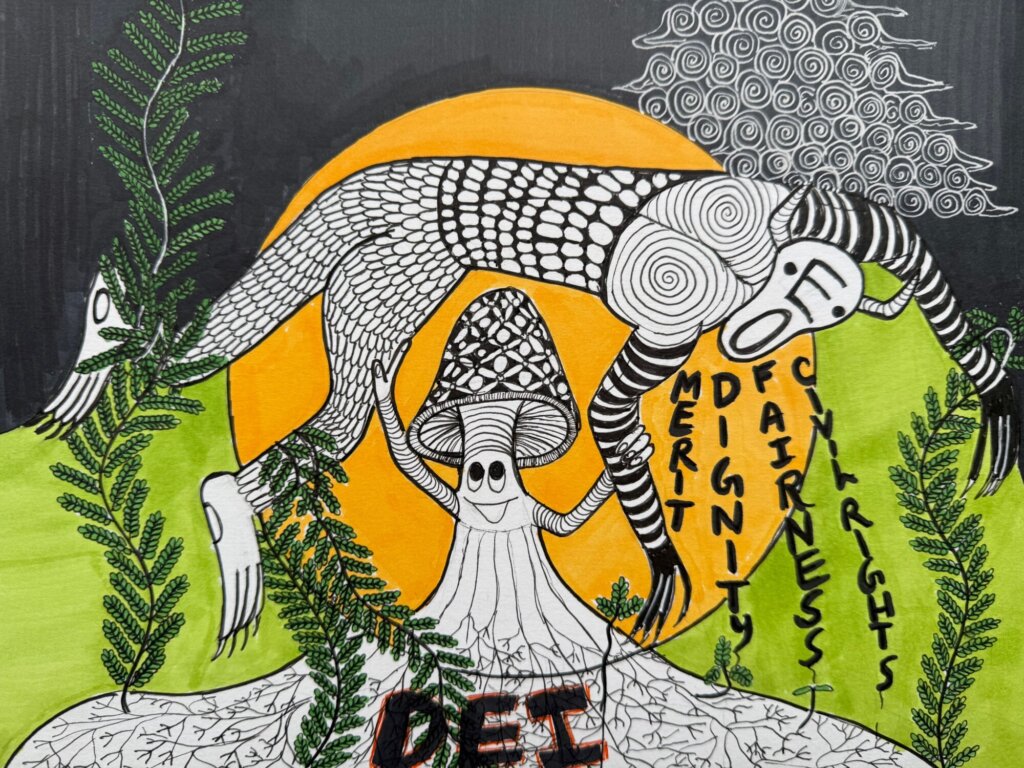

Read full post about DEI Jujitsu: Flipping the Backlash to Reframe Our Work