Ava

Published on

02 - 18 - 2016

Ava

Published on

02 - 18 - 2016

On March 1, 2016, in the wake of Delaware North’s exploitation of trademark laws, many of the iconic places in Yosemite National Park—including Curry Village, the Ahwahnee Hotel, the Wawona Hotel, the Yosemite Lodge, and Badger Pass Ski Area—will be renamed. There are (understandably) many people and organizations who are frustrated with Delaware North’s monetization of a public good.

But in all the public outrage, we may be overlooking an opportunity to look deeper into history of place-naming. A toponymn refers to the name of a place, and often encourages us to investigate the historical context in which the place is named. Behind every name bestowed upon valleys, peaks, rivers, meadows, and even structures lies a story. So every map we pore over as we prepare to explore our public lands is riddled with often overlooked stories. And just by scratching the surface of toponymns, we can find a hidden history that alludes to our public lands’ complex and sometimes unsavory history.

We first came to understand the importance of toponymns while watching Ken Burns’ documentary, “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” Within the first 20 minutes of the documentary, the narrator tells us the story of how the Mariposa Battalion entered into what we now know as Yosemite Valley. Wanting to claim the valley for themselves, the Battalion waged a war against the Ahwahnechee tribe, who referred to the valley they inhabited as Awooni, meaning “gaping mouth” (alluding to the appearance of the valley walls from their village on the valley floor).

After violently claiming the valley, the Battalion decided to name the place “Yosemite.” The narrator tells us that “Yosemite” is the Anglicized form of a word the Battalion heard the Ahwahnechee frequently cry during the violence. The Battalion thought that Yosemite might be the indigenous name for the valley. But Yosemeatea actually meant “killers.” In the irony of all ironies, the Mariposa Battalion unwittingly had named the valley that they forcibly dispossessed from the Ahwahnechee after . . . themselves.

The story is at best chilling and illuminating (especially in light of the documentary title, “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea”). It opens up an often closed conversation about how the US came to possess the lands that are now our public lands; the lands that are supposed to be the pride of the American West, the lands that are supposed to be welcoming to all citizens. It uncovers a reality that disrupts America’s romanticized view of these lands.

The hidden stories behind names have recently prompted the renaming of several national landmarks. In the last year alone, President Obama called for Mount McKinley to be renamed Denali, the original indigenous name of the peak, in an effort place the indigenous presence in the forefront of the American psyche. Coon Lake in the North Cascades, literally named with a racial slur, was renamed Howard Lake after the African American prospector. These are just two examples of a long list of toponyms that are being lobbied to change to reflect indigenous presence.

Of course, uncovering stories and renaming toponyms is just the beginning, but we cannot start if not at the beginning. In light of new (for some) information, we not only have an opportunity, but a responsibility to disrupt norms that have upheld a myopic understanding of our public lands.

Dear Avarna community, We’re only four months into four years of this presidential administration, and the attacks on everything our…

Read full post about Staying the Course: On EOs, Education, ERGs, and SailingAvarna Community, It is with nearly all the emotions you might find in an emotions wheel that I am announcing…

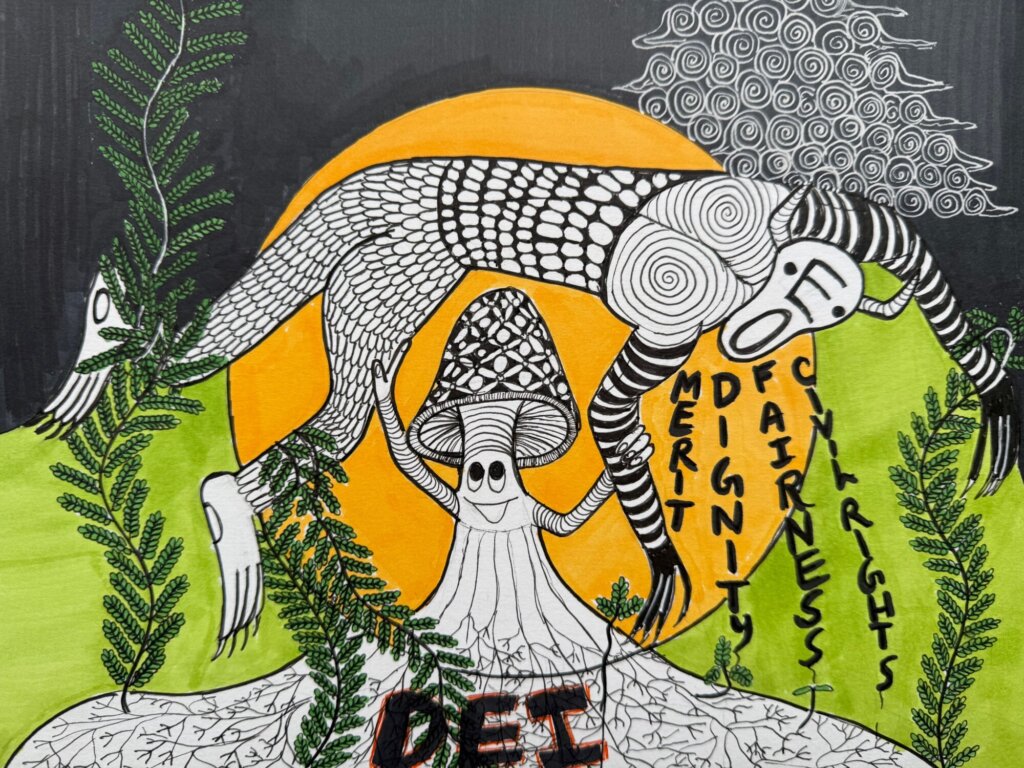

Read full post about Farewell, AvarnaThe current administration’s anti-DEI Executive Orders have sparked varied responses in the nonprofit and private sectors—some organizations are defending DEI…

Read full post about DEI Jujitsu: Flipping the Backlash to Reframe Our Work